Afghanistan approaches the midpoint of 2025 navigating a precarious geopolitical theatre. Internally, the Afghan government continues its drive for centralisation and ideological homogenisation. Externally, Kabul is pursuing a methodical campaign of diplomatic normalisation, threading ties eastward and southward even as Western recognition remains withheld. Yet a regional conflagration driven by Israel’s intensifying confrontation with Iran now threatens to undermine these painstaking gains.

Domestic consolidation

The Taliban have continued their drive toward centralisation through monopolising an already-tight political space. An earlier edict that banned all political parties came to bear its full weight in a crackdown on Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami in April. The two parties have long shared a tense and uneasy relationship. Partially allied in the fight against the US occupation, differences have come to the fore following the Taliban’s 2021 takeover; the latest episode included purported arrests of staff and closures of offices after Hekmatyar was evicted from his government-owned domicile in Kabul’s Darul Aman area in 2024. Alternative Islamist currents, particularly inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood, continue to be seen as threats to religious legitimacy.

These actions accompany continued emphasis on ideological purity. In the first Eid sermon marking Eid al-Fitr (April 2025), Amir Hebatullah Akhundzada framed the occasion as a ‘golden opportunity’ for national unity and ideological consolidation. He praised Afghan security forces, in particular, officials from the Amr bil Ma’roof, or Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. Extolling their work, the Amir invoked the Qur’an to reinforce the importance of the Sharia. That, in turn, was a firm statement of support for a Ministry whose exact role remains polarising. ‘The Ministry of Vice and Virtue,’ the Amir expounded, ‘[as well as] the Mujahideen and security institutions must be supported with sincerity.”

The khutba delivered on Eid al-Adha (7 June 2025) saw the Amir redouble his calls for unity through absolute obedience to Sharia which, implicitly, meant absolute obedience to his rule. He warned against dissent, including against his own officials, whilst declaring foreign interference intolerable. He invoked the sacrifice of Prophet Ibrahim (peace and blessings be upon him) to extol loyalty. Economic autarky and rejection of Western legal models were, once again, positioned as prerequisites for the twin pillars Afghan sovereignty and Islamic legitimacy. ‘Our nation will never accept Western legal models… our salvation lies in full implementation of Sharia.’

Yet domestic order is less assured than broadcast. Intra-government frictions simmer behind the veil; ISKP and anti-Taliban insurgents persist in outlying districts; and fresh cross-border clashes with Pakistan around Torkham and Helmand have cost lives and displaced civilians.

Diplomatic strides

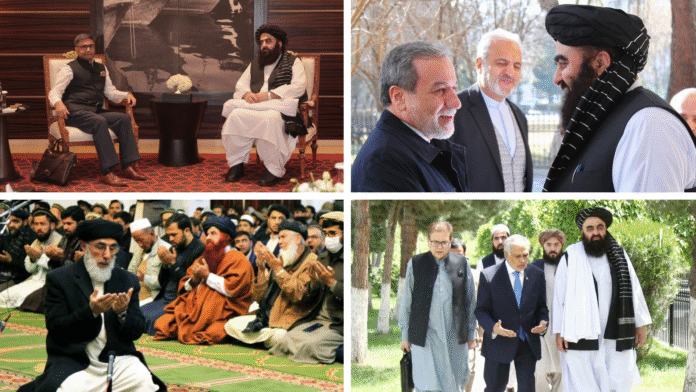

Diplomatic momentum has quickened. In June, Turkey accepted a new Taliban ambassador. As part of widening Russo-Afghan normalisation, Kabul attended an International Economic Forum in St. Petersburg, whilst a month earlier, in Uzekistan, Afghan representatives joined the Termez Dialogue on Connectivity, affirming its role as a transit hub.

In late May, Pakistan restored ambassadorial-level ties and dispatched Deputy Prime Minister Ishaq Dar to Kabul, reinforcing bilateral cooperation. The positive development followed an informal trilateral summit in Beijing between the foreign ministers of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and China, in which Beijing is surmised as playing a pivotal role in fostering greater an upswing in troubled relations between Kabul and Islamabad. Whilst the development is undoubtedly positive, their continuation remains heavily dependent on security within Pakistan and, most notably, the TTP. A suicide attack mere days later in Mir Ali, Waziristan, killed thirteen Pakistani troops, and cast a shadow over otherwise positive bilateral momentum.

To the West, Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi became the first senior Iranian official to visit Kabul since 2017. He met Acting PM Hassan Akhund, FM Muttaqi, and Defence Minister Yaqoob. Discussions focused on border security, Helmand water treaty implementation, economic cooperation, and the status of Afghan refugees in Iran. Araghchi emphasised Iran’s commitment to facilitating the return of some 3.5 million refugees—while asserting that “Iran’s security and stability are dependent on the security and stability of Afghanistan.”

The developments reflect a calculated regional normalisation, allowing Kabul greater access to bilateral coordination, infrastructure talks, and regional forums. Ties with the West, however, remain largely at a standstill.

Strategic Alignments

Conflict is a close memory for Afghanistan, but confined to its recent past. 2025, however, has seen conflict become increasingly common across Asia. In April 2025, following an attack on tourists in Indian-occupied Kashmir’s Pahalgam, direct hostilities erupted between India and Pakistan; the former blamed the latter, predictably, for the attack. Amidst the exchange, Afghanistan’s adoption of a careful posture of public neutrality was noteworthy. Despite a rift with Pakistan and both land and maritime trade with India through Chabahar and Attari, Kabul studiously avoided aligning with Delhi. It also avoided any alignment with Pakistan.

This neutrality, as Sangar Paykhar noted, is not mere passivity but calculated positioning, allowing the Afghan government to extract maximum concession from both states while avoiding entanglement in subcontinental geopolitics. Given Pakistan’s subsequent upgrading of ties with Kabul as well as Delhi’s appreciation for Afghanistan’s stance, it would seem the calculated positioning paid resounding dividends. Afghanistan presented itself not as an ideological ally, but as a logistical corridor.

To its West, Iran was soon to become embroiled in an exchange with Israel that commenced with Israel’s commencement of an air offensive against Iranian military targets. Condemning the Israeli attacks and expressing solidarity with Iran, Afghanistan cooperated in facilitating the return of Iranian pilgrims from Saudi Arabia through Afghan territory, waiving visa requirements and providing logistics in Herat. The initiative was publicly welcomed by Iranian Sunni cleric Abdul Hamid, who praised Afghanistan for its security as well as for supporting Iranian citizens during their return from Hajj. Afghanistan’s cooperation was hardly reciprocated, as Afghan refugees in Iran were scapegoated for Tehran’s intelligence failures, and Iranian authorities continue mass deportations of Afghan refugees, straining border capacities and exacerbating humanitarian pressures.

Another element to the Israeli-Iranian exchange that affected Afghanistan, which was not a participant, was the fate of Iran’s Chabahar Port. Chabahar has long been touted as a potential alternative and rival to Karachi, whose development could upend regional trade patterns in the benefit of Tehran as well as Kabul: keen to decrease its reliance on Pakistan’s Karachi, as well as India: Pakistan’s archrival. India’s interest in Chabahar’s wellbeing, meanwhile, contrasts strongly with its strong ties with Israel.

A Perilous Half Year

Domestically, Afghanistan’s economy remains heavily reliant on agriculture, small-scale trade, and foreign humanitarian aid. The Afghan government touts a 10 percent increase in wheat production, in what Agriculture Minister Ataullah Omari reiterated as a push toward economic autarky. The same push for autarky also saw Kabul cancel, in a first, a twenty five year contract previously won by a Chinese company.

The arc of Afghan diplomacy in 2025 has navigated challenges east and west. Kabul’s trajectory may depend on how successfully it navigates those challenges, but the magnitude of those challenges too. Victim to conflagrations surrounding it, Afghanistan’s balancing act will only grow more perilous amidst the aftershocks of wars not its own.