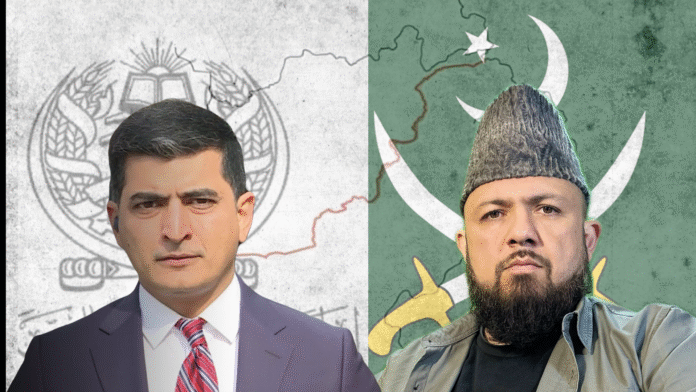

In The Afghan Eye’s latest episode, journalist Ali Mustafa outlines how Pakistan’s domestic turmoil, military dominance, and transactional ties with the United States have combined to produce the region’s current crisis, a fragile ceasefire, collapsing diplomacy, and the real threat of war with Afghanistan.

Airstrikes, Ceasefires, and an Escalating Border War

The conversation begins amid a backdrop of bloodshed. Pakistani airstrikes along the Durand Line have killed civilians, including athletes, and provoked Afghan ground incursions into Pakistani territory. A ceasefire mediated by Saudi Arabia and Qatar briefly held, but soon collapsed following another bombing in Paktika.

For Mustafa, this escalation reflects the bankruptcy of both diplomacy and trust. Decades of suspicion between Islamabad and Kabul have hardened into hostility, fuelled by cross-border militancy and the absence of coherent political strategy. What began as sporadic skirmishes has now evolved into a dangerous cycle of retaliation, with both nations’ militaries acting more out of habit than purpose.

Trump, Imran Khan, and the Rebirth of a Military Alliance

Mustafa traces the roots of Pakistan’s current military alignment with Washington back to the final years of the Trump presidency. Despite Trump’s earlier outbursts against Pakistan, relations between his circle and Pakistan’s military elite began to thaw in late 2024, driven by a web of lobbying by the Pakistani-American diaspora and by Pakistan’s renewed relevance in the war in Ukraine.

Following Imran Khan’s ousting in 2022 and subsequent imprisonment, Pakistani Americans mobilised politically in the US, pressing both Democrats and Republicans to raise human rights concerns. Some of these activists found common cause with Trump’s campaign, viewing his anti-establishment stance as sympathetic to their grievances.

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s military sought to rebrand itself as a valuable partner for the United States, supplying ammunition for Ukraine and reopening channels with American defence contractors. This convergence of interests laid the groundwork for renewed engagement between Pakistan’s generals and Trump’s advisers.

Mustafa describes a transactional revival: the Pakistani establishment offered access to minerals, ports, and even digital ventures like cryptocurrency projects, while Trump’s team offered political recognition. Meetings between senior military officials and Trump associates multiplied, with Pakistan’s leadership seeking legitimacy in Washington that its own people denied it at home.

Diplomacy for Sale: Ports, Minerals, and Political Favour

As these contacts deepened, the Pakistani military’s overtures to the Trump camp expanded beyond diplomacy. Mustafa recounts reports, unverified but persistent, of offers involving mineral rights, maritime access near Gwadar, and participation in Trump-linked investment networks.

Such overtures, he suggests, reveal the military’s search for international validation. With Pakistan’s democracy effectively paralysed and its economy dependent on external lifelines, the generals turned to Washington for both political protection and financial relief. In return, they presented Pakistan as the West’s indispensable ally against instability in South Asia.

This strategic opportunism, however, came at a price. By entangling Pakistan in American power plays, from the Abraham Accords to the Gaza peace plan, the military establishment risked alienating its own public and allies alike. Mustafa sees this not as diplomacy but as dependency disguised as pragmatism.

The TTP Dilemma: Manufactured Chaos and Managed Risk

A large portion of the discussion revolves around Pakistan’s war with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the perception that Islamabad has turned militancy into a manageable threat. Mustafa acknowledges a long pattern: when violence escalates, it justifies the military’s dominance; when it subsides, it strengthens its image as protector.

During Imran Khan’s tenure, negotiations between the Pakistani government and the TTP, facilitated by Kabul, collapsed. The talks ended with assassinations and renewed fighting. Since then, Pakistan’s approach has reverted to aerial bombardments and deflection: blaming Afghanistan for harbouring militants while refusing to acknowledge the internal roots of the insurgency.

From an Afghan perspective, this logic appears cynical. Attacks deep inside Pakistani territory are attributed to Afghan sanctuaries, yet vast stretches of land between those areas and the Durand Line remain under Pakistan’s own control. Paykhar notes that such contradictions expose a deeper problem: Pakistan’s military treats insecurity as both a threat and a resource. It sustains its budget, its legitimacy, and its monopoly on power.

A History of Double Games

To understand this duplicity, Mustafa rewinds to the 20-year “War on Terror.” Pakistan, he reminds listeners, positioned itself as both a US ally and an enabler of the Afghan Taliban. It hosted militant groups while accepting American aid to fight them. It fenced the Durand Line while denying its permanence. And it fought insurgents in its tribal areas while facilitating others across the border.

These contradictions, he argues, were never strategic; they were transactional. Pakistan’s military sold cooperation to the highest bidder, first the US, now potentially China or Trump’s future administration, without regard for long-term stability. The result is what Mustafa calls “cycles of chaos”: each phase of short-term gain leads to deeper institutional decay.

The same calculus, he notes, underlies the current confrontation with Afghanistan. The military’s short-term alliances, its overreach into civilian governance, and its suppression of dissent have left Pakistan dangerously brittle. The state’s survival instincts, not national interest, dictate policy.

China, the United States, and a Fraying Balance

A crucial segment of Mustafa’s analysis concerns Pakistan’s uneasy balancing act between Beijing and Washington. While China has long been Pakistan’s most reliable partner through the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), recent months have revealed fissures.

Mustafa points to China’s discomfort with Pakistan’s renewed military engagement with the US and reports of American-linked companies acquiring stakes in mineral extraction projects once earmarked for Chinese investors. He highlights Beijing’s recent tightening of export controls on mining equipment as a possible signal of displeasure.

More significantly, China had sought to mediate between Islamabad and Kabul through trilateral talks earlier this year. Yet, as violence flared and Pakistan gravitated back toward the American orbit, Beijing’s mediation faded. Mustafa views this as evidence of Pakistan’s unreliability: a state unable to sustain consistent alliances, perpetually oscillating between competing powers.

Trump’s Shadow and the Return of Bagram

The discussion also touches on Donald Trump’s repeated claims of negotiating with the Taliban to reclaim Bagram Air Base. Mustafa treats these assertions with scepticism. Paykhar notes that there is no evidence of such talks, and the Taliban have publicly denied them.

Yet the symbolism matters. Trump’s rhetoric, combined with Pakistan’s simultaneous airstrikes and overtures to Washington, feeds Afghan suspicions that these operations serve a broader agenda: to reinsert American influence into Afghanistan via Pakistan. The choice of Qatar, home to US Central Command, as the site of mediation only amplifies those doubts.

Mustafa dismisses the idea that Bagram itself was on the table in Doha, but he concedes that Pakistan’s alignment with American interests, through defence pacts with Saudi Arabia and cooperation on regional security, has made it part of a wider architecture designed to contain China and manage the Middle East. Afghanistan, caught in this geopolitical contest, risks becoming collateral once again.

Pakistan’s Internal Meltdown

Ali Mustafa’s critique ultimately returns home. The Pakistani military, he argues, has not only militarised foreign policy but hollowed out domestic politics. Over the past three years, it has manipulated elections, suppressed civilian institutions, and silenced dissent through military courts.

The judiciary, the press, and even provincial autonomy have been systematically eroded. In Balochistan, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings persist. Meanwhile, the economy teeters under debt, inflation, and international scrutiny. Mustafa portrays this not as governance but as managed collapse, a state surviving on inertia and repression.

He warns that Pakistan’s current path, alienating Afghanistan, provoking India, and overplaying its ties to Washington, may soon exhaust even its most loyal allies. China’s patience, too, has limits. A strategy built on perpetual crisis, he says, is not sustainable.

Afghanistan and Pakistan: Bound by Geography, Divided by Politics

Despite the grim outlook, Mustafa ends on a reflective note. Pakistan and Afghanistan, he reminds listeners, are neighbours bound by shared history, migration, and suffering. Millions of Afghans were born and educated in Pakistan; the social and cultural ties between the two societies are undeniable.

Yet both countries remain hostage to the politics of mistrust. Pakistan’s militarisation of foreign policy and Afghanistan’s rejection of imposed dependency have hardened attitudes on both sides. The challenge, he suggests, is to transcend the language of accusation and rediscover the mutual interests, trade, connectivity, and regional stability that once defined their relationship.

Conclusion: A Reckoning Deferred

Ali Mustafa’s analysis paints Pakistan as a state trapped between its own insecurities and the ambitions of others. Its generals seek validation abroad while losing legitimacy at home. Its alliances shift with global winds, but its neighbourhood remains constant, and unforgiving.

The current crisis along the Durand Line is not an aberration but the outcome of decades of double games. Whether Islamabad learns from this history or repeats it will determine not only Pakistan’s future but the stability of the entire region. As Mustafa concludes, powers like America come and go, but neighbours remain. Pakistan’s greatest challenge, therefore, is not Afghanistan—it is itself.