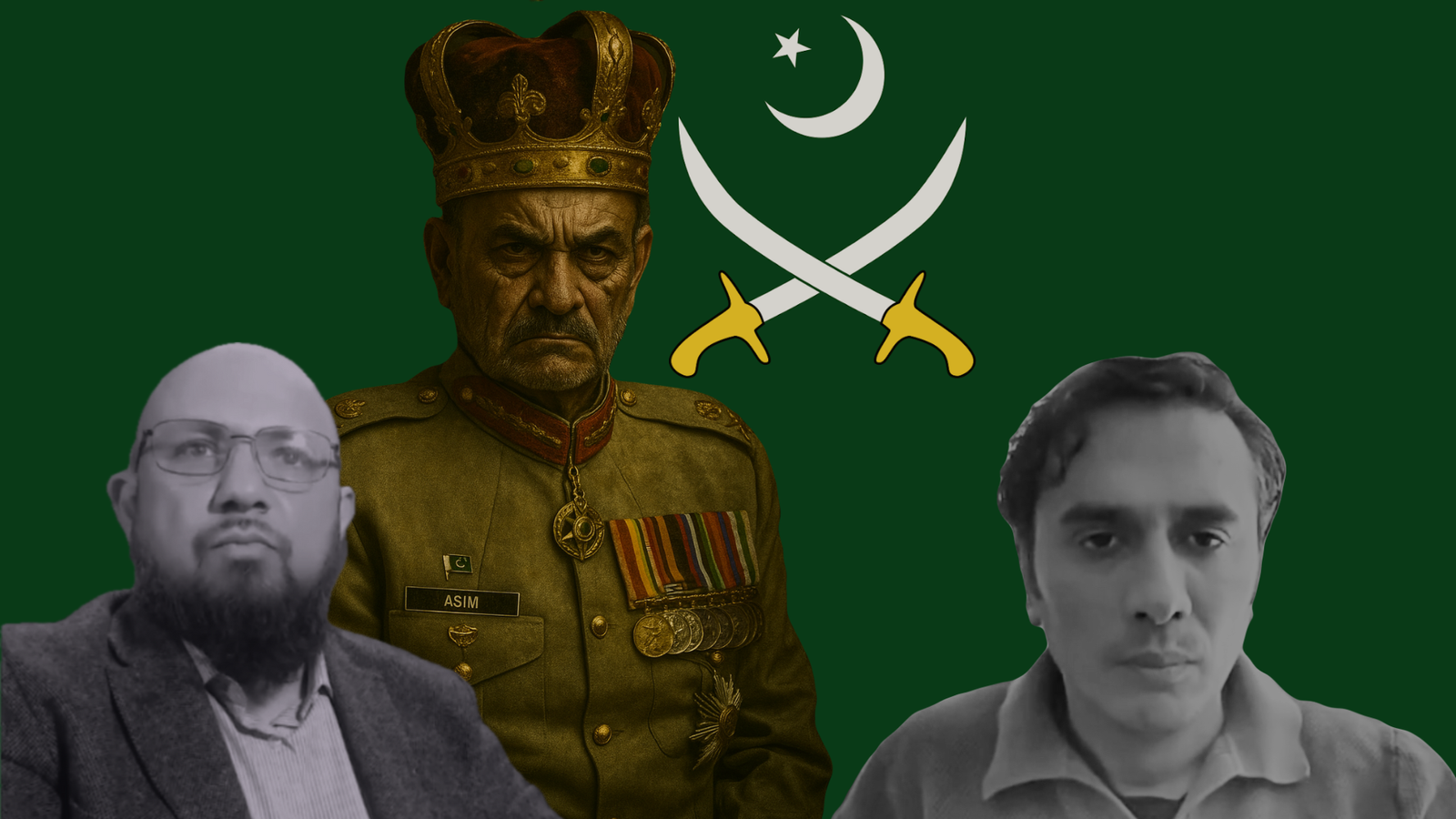

‘Even kings did not claim immunity for life,’ says Pakistani journalist Waqas Ahmed, describing a constitutional change that may transform Pakistan’s political structure. Speaking on The Afghan Eye Podcast, Ahmed details how Field Marshal Asim Munir’s 27th Amendment threatens the foundations of Pakistan’s fragile democracy and reshapes its relations with Afghanistan.

The 27th Amendment: From Army Chief to Field Marshal

According to Ahmed, Pakistan’s 27th Amendment effectively rewrites the 1973 Constitution. It elevates the Chief of Army Staff to the rank of Field Marshal for life, providing total legal immunity from prosecution.

‘This amendment is being pushed by unelected figures,’ Ahmed says. ‘It erases the guardrails that kept the military accountable.’

Historically, Pakistan’s military shared top-level decision-making through the National Security Committee and Joint Chiefs of Staff, ensuring checks between the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The new amendment dismantles those structures, giving Munir exclusive control over national security, policymaking, and most alarmingly, Pakistan’s nuclear command.

Ahmed describes this shift as the formalisation of what has long existed informally: the dominance of Pakistan’s army over civilian politics.

Imran Khan’s Ouster and Washington’s Shadow

The roots of this constitutional coup trace back to February 2022, when Prime Minister Imran Khan was removed from office. Ahmed alleges that Khan’s insistence on an independent foreign policy and his visit to Moscow on the eve of the Ukraine war angered Washington.

‘The Americans decided that this guy was too independent,’ Ahmed claims, citing leaked diplomatic cables published by The Intercept. ‘They told the Pakistani military: remove Imran Khan, and all will be forgiven.’

Following his removal, Khan’s supporters, primarily Pakistan’s middle class, were crushed through arrests, censorship, and mass intimidation. Ahmed argues that the ongoing constitutional changes are designed to ensure no civilian can challenge the military again.

The Hard State: From Informality to Cruelty

Ahmed identifies a philosophical shift under Asim Munir’s rule. The General envisions Pakistan as a ‘hard state’, a term he has publicly used. For decades, Pakistan’s informal social networks provided ordinary citizens with limited protection against state excesses. Now, Ahmed says, those safety nets are being dismantled.

‘The one word that describes what’s happening in Pakistan is cruelty,’ Ahmed remarks. He links the state’s recent mass deportation of Afghan refugees to this hardened attitude:

‘In the past, if a policeman harassed an Afghan family, you could call a local official and stop it. Now everyone is ordered to be cruel.’

This shift has devastated communities that lived in Pakistan for decades. Families who built homes, opened businesses, and contributed to local economies are now being expelled without due process. Ahmed views this not as mismanagement but policy by design.

The Afghan Refugee Expulsions: Political Theatre with Global Aims

The deportation of Afghan refugees, Ahmed argues, serves a dual purpose. Domestically, it fuels nationalist sentiment and distracts from economic collapse. Internationally, it repositions Pakistan as a partner to Washington in a new geopolitical bargain.

‘Pakistan wants to be close to America again,’ he says. ‘By creating conflict with Afghanistan, they can present themselves as indispensable in the region.’

The strategy recalls earlier decades when hosting Afghan refugees and managing the war next door brought in foreign aid. But this time, the financial and moral costs outweigh the gains. Unlike the Cold War era, Western governments are no longer eager to fund Pakistan’s regional manoeuvres.

The Economic Meltdown and Middle-Class Collapse

Ahmed highlights Pakistan’s economic implosion since Khan’s ouster. Inflation, debt, and capital flight have gutted the middle class. ‘Ten percent of Pakistan’s middle class fell below the poverty line,’ he notes.

This collapse, he argues, was not accidental. The military perceived the middle class, Imran Khan’s strongest base, as a political threat. By impoverishing them, the establishment aimed to depoliticise society. Yet the result has been the opposite: foreign investors are fleeing, leaving an economy in freefall.

Colonial Legacy of the Pakistani Military

Ahmed traces the Pakistani army’s authoritarian reflexes to its colonial British origins. Formed as part of the British Indian Army, its structure and ethos remained unchanged after 1947.

‘They still see themselves as rulers, not servants,’ Ahmed says. ‘They inherited the colonial mindset, those who wear the uniform are superior to civilians, to the poor, to anyone who does not speak English.’

This institutional memory, he argues, explains the military’s enduring dominance and its indifference to democratic norms.

Pakistan’s Nuclear Command: A Dangerous Centralisation

Perhaps the most alarming element of the 27th Amendment, Ahmed warns, is the transfer of nuclear command to the Field Marshal alone. Previously, Pakistan’s nuclear assets were under the Strategic Plans Division supervised collectively by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

‘Now, all guardrails are gone,’ Ahmed says. ‘Munir will control Pakistan’s nuclear weapons directly. It means the nuclear question is back on the table.’

Under the new system, Munir could theoretically negotiate Pakistan’s nuclear status with foreign powers, something impossible under previous constitutional arrangements. Ahmed recalls that former army chief Qamar Javed Bajwa had proposed dismantling parts of the nuclear programme in exchange for Western aid. Munir’s amendment makes such negotiations far easier.

Unchecked Power and Regional Consequences

If history is a guide, Ahmed suggests, absolute power rarely lasts. ‘Every king who claimed immunity for life met a miserable end,’ he says. Yet, in the short term, Pakistan faces the prospect of one-man rule.

For Afghanistan, the consequences are serious. A militarised Pakistan under Munir may pursue confrontation along the Durand Line to justify its alliance with Washington. Refugee expulsions, air strikes in border provinces, and propaganda campaigns against Kabul may escalate.

Still, Ahmed believes the region’s future need not be bleak:

‘Pakistan should have closer relations with Afghanistan and India. We have enough for everyone. We do not have to fight.’

His warning is clear: power pursued as an end in itself is unsustainable. Pakistan’s future stability, and its relationship with its neighbours, depends on rediscovering the balance between strength and compassion.