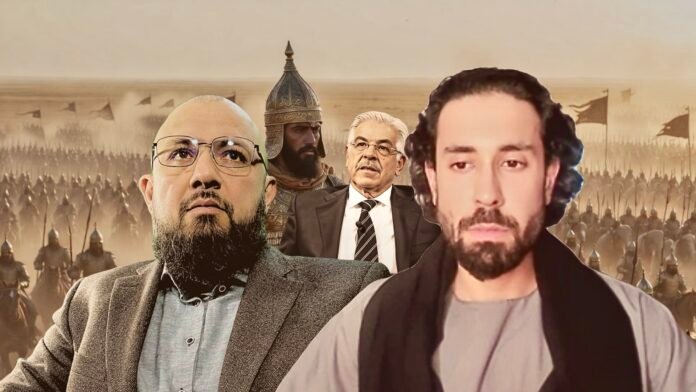

The latest episode of The Afghan Eye Podcast brings host Sangar Paykhar and Ahmed-Waleed Kakar into a wide-ranging discussion on Pakistan’s historical myths, its brewing identity crisis, and the central but simultaneously uncomfortable role of Afghanistan in both.

Pakistan’s mythmaking and Mahmud of Ghazni

The conversation begins with Pakistan’s relationship to one of its most visible historical symbols: Mahmud of Ghazni. In a recent Pakistani podcast, Defence Minister Khawaja Asif reiterated the need to craft a ‘national narrative’ and lionise ‘local figures’ as opposed to ‘foreign.’ This was a reiteration of Asif’s position, first articulated in an interview last year, wherein he controversially described 11th century century emperor Mahmud Ghaznawi as a mere ‘plunderer’ and questioned why Pakistani missiles are named after him. This remark is the thread from which the episode systematically unravels Pakistan’s broader narrative about itself.

For decades, Pakistan has drawn on a long line of Muslim rulers to tell a national story that precedes the 1947 state. Figures such as Muhammad bin Qasim, Mahmud of Ghazni, the Delhi sultans, the Ghoris, the Mughals and Ahmad Shah Durrani appear as a continuous chain of Muslim rule in the subcontinent. Pakistan’s textbooks, public monuments and missile names have reflected this adoption of older empires as spiritual and ideological ancestors.

In this narrative, Mahmud of Ghazni is not simply a raider of temples. He is an empire builder who took Islam into parts of northern India, a patron of scholars, and a ruler whose campaigns helped redraw the religious map of the region. For many Muslims, he was the archetypal ‘idol-breaker’; for many Hindus, he is a villain whose name is invoked alongside destruction and humiliation. Pakistan has historically placed itself firmly on one side of that divide.

Khawaja Asif’s comment therefore does not only reclassify Mahmud as a looter. It cuts against the official story in which Pakistan presents itself as heir to Muslim polities that came from Afghanistan and Central Asia into the subcontinent. If Pakistan now accepts the vocabulary of ‘invader’ and ‘plunderer’, it implicitly moves closer to the Hindutva framing of those centuries as foreign occupation.

The episode situates this revisionism within a broader pattern of nation states ‘nationalising’ history. Every modern state selects which figures to elevate and which to sideline. Afghanistan claims the legacy of figures such as Ahmad Shah Durrani, Mahmud of Ghazni and even Jalaluddin Rumi as part of a shared Islamic civilisational paradigm that predates the Westphalian state. Pakistan, too, has long done this. What is new is the apparent willingness of senior Pakistani officials to disown precisely the figures that helped distinguish Pakistan from ‘India’ in the first place. In national terms, this would be tantamount to cutting off its Islamic nose to spite its Afghan face.

From Islamic vanguard to donor-friendly nationalism

The episode then moves from mythmaking to the present day. Ahmed-Waleed Kakar and Sangar Paykhar argue that Pakistan’s reassessment of its historical heroes mirrors a deeper shift in its political and economic orientation.

For most of the Cold War and the post-9/11 period, Pakistan could present itself as an Islamic vanguard. Against the Soviet-backed regime in Kabul, it was the staging ground of Afghan jihad. Against the War on Terror’ it claimed, with mixed results, to be an indispensable ally with unique access to Islamist networks. Religion, geopolitics and the Pakistani military’s own institutional interests aligned.

That alignment has broken down. Pakistan is heavily indebted, reliant on International Monetary Fund programmes and repeated bailouts from Gulf states and Western partners. Its strategic value as a ‘frontline state’ has declined since the end of the foreign occupation of Afghanistan. Even China’s enthusiasm has its limits.

In such circumstances, the Pakistani establishment faces strong incentives to rebrand. A state that once emphasised its Islamic credentials increasingly slides toward authoritarianism because, and not in spite of, its growing adoption of the the language of ‘moderation’, ‘tolerance’ and ‘progressive’ reform . Policies on social issues, gestures towards religious minorities, and openness to regional realignments are read in the episode as part of a bid to appear more palatable to Western and Gulf donors.

Khawaja Asif’s framing of Mahmud of Ghazni as a looter fits neatly into this turn. Casting distance between present-day Pakistan and pre-modern Muslim conquerors is a way to reassure both domestic liberals and foreign partners that Pakistan will not ground its identity in militant religious narratives. It signals a move away from trans-regional Islamic history towards a narrower, territorial nationalism that looks closer to that of its neighbours.

However, the hosts emphasise a crucial contradiction. Even as Pakistani officials denounce older Muslim rulers in the language of plunder and invasion, the Pakistani army continues to invoke Islamic symbolism for its own legitimacy. The current army chief is styled not merely as a general, but as ‘Hafiz Syed Asim Munir Shah’: a memoriser of the Qur’an and claimed descendant of the Prophet. Religious titles and imagery continue to surround the military’s public image.

This duality: liberal-nationalist rhetoric for donors juxtaposed with Islamic symbolism for a domestic audience, is evidence of an elite that has lost confidence in its founding story. Pakistan wishes to step away from the Islamic imperial genealogy that once justified its separation from India, but it has not yet found a stable replacement narrative that resonates with its own population.

Afghanistan at the centre of Pakistan’s identity crisis

Throughout the episode, Afghanistan is not treated as a peripheral neighbour but as the unseen protagonist in Pakistan’s identity crisis.

First, there is the simple historical fact that many of the figures Pakistan once celebrated as its ancestors are rooted in Afghan or Central Asian history. Mahmud of Ghazni ruled from what is today eastern Afghanistan. Ahmad Shah Durrani, whose name graces Pakistani missiles, founded the modern Afghan state. Even the very acronym ‘Pakistan’ was originally drafted with ‘Afghania’: then referring to Khyber Pashtunkhwa (formerly the North West Frontier Province) as one of its components.

In this reading, Pakistani national identity has always depended heavily on Afghan and Central Asian heritage to distinguish itself from ‘India’. To abandon Mahmud or Ahmad Shah as ‘foreign plunderers’ is therefore far more than an act of historical revision. It amputates Pakistan from the very civilisational space that once breathed life into its national tale and gave it ideological depth.

Second, the Islamic Emirate in Kabul now occupies an awkward place in Pakistan’s religious imagination. When Kabul was ruled by communists or Western-backed technocrats, Pakistan could present itself as the authentic Islamic power in the region. After the Taliban’s return in 2021, that comparison became far less comfortable.

Whatever one thinks of the Emirate’s policies, its survival against United States and NATO pressure has given it a kind of religious and symbolic legitimacy among many ordinary Muslims, including inside Pakistan. By contrast, the Pakistani military establishment is widely seen as having facilitated foreign military operations, and as having turned its coercive apparatus inward against its own former allies and leaders.

In one of the podcast’s most striking points, Sangar and Ahmed-Waleed discuss reports that Pakistani officials sought a religious decree from the Afghan leadership against militant attacks inside Pakistan. For decades, Islamabad presented itself as the source of religious guidance and support for Islamist causes inside Afghanistan. To request a fatwa from Kabul is an admission that the Afghan Emirate holds the key: an Islamic legitimacy that Pakistan’s rulers sorely lack.

Third, Afghanistan and Pakistan are deeply entangled societies. Millions of Afghans have lived, studied or worked in Pakistan over the last forty years. Pashtun communities straddle the Durand Line, with shared poets, religious scholars and tribal networks. Kabul has never disowned Pashtun figures on the Pakistani side of that line as ‘foreigners”’ The Pashto literary canon moves back and forth across it.

The episode points to smaller symbols as well. The qaraqul cap popularised by Muhammad Ali Jinnah has long been a Central Asian and Afghan headgear, worn a century earlier by figures such as Mahmud Tarzi. The visual icon of Pakistan’s founder, in other words, is itself a quiet borrowing from the Afghan and Central Asian cultural sphere.

Against this backdrop, Pakistani attempts to rhetorically detach themselves from Afghan history sound, in the hosts’ words, like a petulant child declaring ‘I am not your child any more’ to its own parents. Politics may push Islamabad and Kabul into periods of hostility, but the underlying historical and social fabric does not disappear.

Religious legitimacy after the Emirate’s return

A central theme of the conversation is the idea of religious legitimacy and how Afghanistan’s recent history has destabilised Pakistan’s claims.

Modern nation states, the hosts argue, always seek to control the scope of religion. Whether in Europe or in South Asia, it is the state that decides where religious law applies, how religious institutions are regulated, and when religion must retreat behind the demands of ‘national interest.’ Pakistan, despite its Islamic vocabulary, has followed this pattern. The military and bureaucracy have repeatedly used Islamic symbolism while maintaining a firm monopoly on real power.

During the Afghan jihad and the post-9/11 insurgency, this arrangement worked relatively smoothly. Pakistan could outsource violence to non-state actors in Afghanistan while claiming to be an Islamic guardian state on the international stage. Domestic religious movements could be co-opted, channelled, or suppressed as needed.

The victory of the Taliban against a foreign-backed government in Kabul has complicated this calculus. The Emirate, whatever its internal complexities, presents itself as an explicitly Islamic political order that has survived the combined efforts of the world’s most powerful military alliance. For Pakistani Islamists and for many ordinary believers, this is a powerful symbol.

Pakistan’s rulers, by contrast, now face a paradox. To maintain their relationships with Western powers and international financial institutions, they must present themselves as pragmatic and moderate. To maintain their internal legitimacy, they still rely on religious vocabulary and imagery. The arrangement rests on a delicate balancing act between the mosque and IMF boardroom.

In this context, Pakistan’s turn away from figures such as Mahmud of Ghazni is not merely about historical taste. It is a sign that the old story: Pakistan as a champion of Islam and custodial heir of centuries of Muslim rule, no longer fits the realities of power and patronage. The Afghan precedent makes that dissonance painfully clear.

Entangled societies beyond the Durand Line

The episode closes its analytical arc by returning to the geography that underpins these arguments. The line imposed by British imperial authorities and known as the Durand Line is treated in the conversation as a political fact but not a civilisational boundary.

On both sides of this line live Pashtun communities who share language, tribal bonds and religious networks. Afghan refugees have left deep cultural and economic footprints in Pakistan’s cities and border regions. Pakistani madrassas, markets and media have shaped Afghan politics in turn.

The hosts stress that identity in this space has never been contained neatly within state borders. Afghan intellectuals have long acknowledged and celebrated Pashtun writers, scholars and saints born on the other side of the Durand Line. Afghan and Pakistani histories interlock, overlap and sometimes clash, but they do not exist in isolation.

In this light, Pakistan’s present attempt to draw a sharp distinction between itself and Afghanistan, whether through the language of ‘plunderers’ in the past or of ‘troublesome neighbours’ in the present, is both ahistorical and self-defeating. It may bring short-term diplomatic convenience or donor approval, but it deepens the underlying identity crisis.

What Pakistan’s identity crisis means for the region

The Afghan Eye episode ultimately presents Pakistan’s identity crisis as more than a domestic drama. When a state that was founded on the two-nation theory begins to question the very Muslim emperors that underwrote that theory, the implications extend far beyond one minister’s soundbite.

If Pakistan continues down a path that embraces Hindutva-style descriptions of pre-modern Muslim rule while disowning its Afghan and Central Asian connections, it risks hollowing out the philosophical basis of its own existence. It will become merely another post-colonial state carved from British India, bound together by little more than shared institutions and a powerful army.

Afghanistan’s role in this story is impossible to erase. It is the source of many of the historical figures Pakistan once celebrated, the home of a neighbouring Islamic political project that now outflanks Pakistan in symbolic terms, and the everyday partner in a dense web of cross-border ties that no fence along the Durand Line can finally sever.

Listeners to the podcast are left with a sobering conclusion. Pakistan can recalibrate its diplomacy, refine its rhetoric and revise its textbooks, but it cannot escape the Afghan shadow without also unmaking much of what has made Pakistan Pakistan. How it resolves that tension will shape not only its own future, but also the stability of the entire region.